Zhurnalnaya Roublennaya: A Poor Man's Futura

Ivar Sakk, Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

Everyday designs using Zhurnalnaya roublennaya

Type production in the young Soviet Union

In the communist period, Soviet consumer goods were limited both in number and in regards to aesthetic options to choose from. It was the same with typefaces for books, posters, newspapers, etc. There were only few of them: the same recognizable characters appeared on greyish cinema tickets and from art books to magazines for children. The geometric sans serif typeface

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Literaturnaya, designed by Anatoly Schukin

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Zhurnalnaya, designed by Nikolay Kudryashov

The first Soviet typeface wasLiteraturnaya(at first named Latinskaya, i.e. "Latin"), based on Berthold's Lateinisch from 1899. It was introduced in 1936, and its lead designer was Anatoly Schukin. In the same year,Zhurnalnayacame out, designed by Nikolay Kudryashov. It was a copy of Linotype's Excelsior (1931), designed by Chauncey H. Griffith. It was a common practice in the Soviet era to copy Western products and rename them, and this was evidently also true for typefaces.

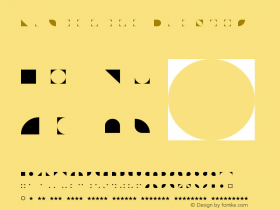

Zhurnalnaya roublennaya

Zhurnalnaya roublennaya(Журнальная рубленая), "Journal Grotesque" or "Magazine Grotesque" in English, was released in 1947, but at that point it supported only Cyrillic-alphabet languages. Roublennaya means "chopped" in Russian, and in this case it is used to mean grotesque, gothic, or sans serif. Soviet sources list Schukin and his colleagues as the designers of the typeface.

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Later Soviet Union specimens of Zhurnalnaya roublennaya with Latin and Cyrillic, designed by Anatoly Schukin

Those sources also mention the German typefaceErbar-Groteskas a prototype, created by Jakob Erbar for the Ludwig & Mayer foundry in 1922. It was very popular in Europe during the 1920s and 1930s. Its geometrically-shaped, rounded characters and sober look fit nicely into the period's visual image. Nowadays, Erbar is only rarely being used. Perhaps the reason is Erbar's absence in the Letraset library in the 1970s, or during the early digital era of the 1990s. Although the color of Erbar in body copy is similar to Roublennaya's, the microshapes of the letters are not the same. Erbar is too fancy to be the sole father of Zhurnalnaya roublennaya.

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Specimens of Erbar-Grotesk, designed by Jakob Erbar

The year 1947 was an exceptional time to release a typeface in Russia. The design process had started before WWII and was finished very shortly after — two years is not a long time after fighting a war of near-total destruction. But the Soviet Union was on the winner's side and removed several of Germany's metal and machine enterprises. Those started a new life in Soviet cities. For example, the Opel car factory's production was

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Berthold-Grotesk

One result of that wasBerthold-Grotesk, which came out in 1928. The type foundry Berthold's typefaces were also produced by the St. Petersburg branch office and stayed in use after the Communist revolution.

From "Schriftkunst. Geschichte, Anatomie und Schönheit der lateinischen Buchstaben" by Albert Kapr. Scan courtesy of Florian Hardwig. License: All Rights Reserved.

Super-Grotesk, designed by Arno Drescher

Another typeface bearing the same early modernist feeling isSuper-Grotesk, designed by Arno Drescher in 1932 for Schriftguss AG in Dresden. Schriftguss, which was located in Eastern Germany, was made a part of VEB Typoart in 1951. With Typoart as the only type foundry in the country after that, Super-Grotesk became the main sans serif typeface of the GDR. In some ways, it is comparable to Zhurnalnaya roublennaya. It shares its proletarian aesthetics and austere image, and the same wide use everywhere in the country due to a lack of alternatives. Shy and grey, overused and underestimated, it became the visual equivalent of communist Germany. It fell into oblivion during the first decade of democracy after the reunification of Germany. But ten years later a wave of Ostalgie arrived, and young typographers started to digitize several fonts that had been in use in the GDR, including Super-Grotesk.

In comparing Zhurnalnaya roublennaya with the above-mentioned typefaces, it is evident that there are a lot of similarities. The shapes of 'a, s, R, and S' are most alike, but the general appearance of the typefaces are also similar. None of the typefaces can be viewed as a direct prototype for Zhurnalnaya, though.

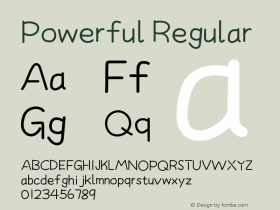

Zhurnalnaya roublennaya as a poor man's Futura

A version of Zhurnalnaya roublennaya supporting Latin-alphabet languages was released in 1962, and became the common sans serif in Estonian printing offices for the next 30 years. It was a newcomer in the Soviet typeface library of Estonia, but mainly, there was simply no choice: the other available sans serif for machine typesetting wasGazetnaya, a typeface based on Franklin Gothic Extra Condensed, which was not suitable for longer text setting. Therefore Roublennaya was mostly used pragmatically, without special aesthetic intention.

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Gazetnaya, based on Franklin Gothic Extra Condensed

In the Soviet-period design magazine Kunst ja Kodu ("Art and Home") for example, the text was set in Roublennaya, but the headlines were in hand-lettered Futura. That was the real typeface in the designers' minds when they designed the layout of the pages. Roublennaya was used in the absence of the desired font, as a poor man's Futura.

Source: http://gt-eesti.com.Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

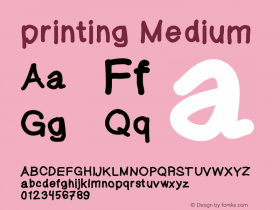

Covers of the book series Loomingu Raamatukogu, 1980–83

Jüri Kaarma was one of the few graphic designers who used Roublennaya intentionally. He designed the magazine Loomingu Raamatukogu ("Looming's Library") and used the typeface on black-and-white covers from 1980–1983. Kaarma trusted the essential quality of a poorly-made Soviet typeface and gave it the main role. To produce more powerful results, Kaarma took the photoset negatives and used the characters oversized, sometimes covering the entire cover. Through this process the quality of the letter contours deteriorated, and this gave an industrial look to the characters.

Ivar Sakk. License: All Rights Reserved.

Spread from Ma olin Jüri Üdi

Another remarkable use of Zhurnalnaya roublennaya dates to 1978, when the same Jüri Kaarma designed Juhan Viiding's poetry book, Ma olin Jüri Üdi ("I was Jüri Üdi"). The modest publication was set in the everyday Soviet typeface, without any additional illustrative elements. Zhurnalnaya roublennaya became the focus of the harsh layout and described, with intense power, the silent nightmare of the poet's childhood years: the Stalinist fifties.

Source: http://gt-eesti.com.Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

Source: http://gt-eesti.com.Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

Cover and spreads of Arhitektid Arhitektuurist

Another interesting use is Arhitektid Arhitektuurist ("Architects' Architecture"). It was designed by Leonhard Lapin and published in 1989. It uses scaled up type on multiple spreads. The resulting rough outlines were then, in some places, manually cleaned up. The stark color contrast drives the inventive layouts. Large and small type is set in two different versions of the same type, with the lowercase 'a' and the apexes of 'A, M, N, W' being the easiest characters to distinguish the two.

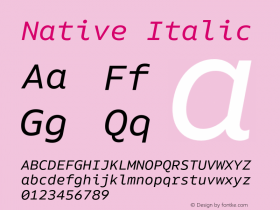

Zhurnalnaya roublennaya and the digital age

At the beginning of the 1990s, when the digital era began, Zhurnalnaya roublennaya fell into obscurity. The Russian type foundry ParaGraph digitized it as early as 1991, but the typeface's drawing quality was very bad. That digital version was called Journal Sans. In 2014 the foundry, now known as ParaType, released both an updated version and a reinterpretation named Journal Sans New. The latter is a very free take on the original design, with elements such as a humanist italic and an inline style.

Source: http://gt-eesti.com.Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

Abikooli Aabits, Estonian ABC book

The lack of a properly made digital version of Zhurnalnaya roublennaya was noticeable in 2007, when the artist

Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

Scans that Moser and Rechsteiner used for the first version of Eesti

As no proper digital version of Roublennaya was available, he used Erbar instead, but in 2009, he helped start a new digitization process through his colleague

Source: http://gt-eesti.com.Grilli Type. License: All Rights Reserved.

GT Eesti specimen

In the six years since, Moser has taken to designing what has now becomeGT Eesti Texthas pointed apexes on 'A, V, W, M, N and Z', unlikeGT Eesti Display. In Soviet specimen books, two cuts are shown as well: one for small uses, and another for larger uses. That's also why GT Eesti Text sports strong ink-traps. The incisions into the lettershapes, wherever two lines meet, help the letters look the right way at smaller sizes, in print and on screen. All styles supports both Latin and Cyrillic Extended languages, including Bulgarian alternates.

The revival of Zhurnalnaya roublennaya is logical and the zeitgeist welcomed the rebirth of this visual phenomenon. It is ironic that a German-prototyped, Russian-manufactured typeface would reappear after being picked up by Swiss designers — who renamed it Eesti.

This article was written by Ivar Sakk, Professor for graphic design at EKA in Tallinn, Estonia, and edited by Thierry Blancpain of Grilli Type. An earlier version was published in issue 21 of Kunstiteaduslikke Uurimusi — Studies on Art and Architecture, the journal of the Estonian Society of Art Historians (pdfs: Estonian with images, English translation). Grilli Type would like to thank Ivar for being a great friend and help to us when we were trying to understand the history of this typeface, as well as for being a great host when we visited Tallinn in February 2015.

闽公网安备35010202000240号

闽公网安备35010202000240号